|

| From the Web comic xkcd.com |

I am one of those that Evgeny Morozov's book talks about -- one who is more likely to use the Internet for entertainment than for furthering some set of my social beliefs. I generally think of myself as a positive person, but this class has shown me that I've fallen more on the pessimistic side of the fence more often than not. Is this because I'm gaining all this wisdom they said I'd get in my 30s? Somehow, I don't think so.

This time, however, the reading for class is written from a skeptical or dystopian standpoint. And, big surprise, I agree with his assessments that the Internet is not the ultimate democratizing tool a lot of Western thinkers believe it is. Morozov's isn't an argument against closing the digital divide by any means, and his isn't an argument against globalized access to the Internet as some may view his pessimism. Instead his view is, in my words, summed up as "it is what it is."

What I found most interesting was an obvious tactic that I'd never thought about -- an authoritarian or repressive government not censoring its Internet use, but instead actively creating content for it (or not limiting access to it) to distract the masses. I didn't connect the prevalence of questionable or pornographic websites in otherwise pretty restricted societies as an aid to further those restrictions, I always just associated it as a result of the of that's society's fragmented foundation. It's a pretty ingenious use of pitting human nature against the humans - don't take away from the people, just give them more of the bad stuff; most won't seek out the healthy food if they're surrounded by sweets.

What I wish Morosov would have done more of was offer more than broad conclusions. I'd like his take on what the government should do (if anything), or who should be part of the Global Network Initiative and what he thinks its main goals should be. He addresses some of these answers in a talk he gave (along with Clay Shirky) at Brown University. It was a quick answer to a student question at 1:05:30 (a long talk, so scroll ahead), at the end of their talk, but it's what I'd like more of.

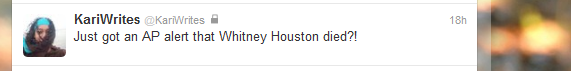

I know that one of my biggest is apathy -- I would not stay up and respond to that person who was "wrong" on the Internet as the subject of the comic would. I'd merely shut my laptop, mutter "idiot" under my breath, and move on. I'd like to think that's what my kindred spirit Morozov would do, too, but considering he already had responses to criticism ready to publish in the paperback version of The Net Delusion, I'm sure he'd sock it away to use as an anecdote in a future book.