The social media scholar danah boyd points out in "Can social network sites enable political action?" that most people use social media to connect with people they already know. That's what happened tonight. I didn't have the race on, nor will I tune into the Oscars most likely, but I'm connected through Twitter or Facebook to friends who will be tuned into these things. How did I find out the race was postponed? Facebook (see?).

|

| George is a good friend who still works in the Sports department in Daytona. It's nights like tonight that I look to the wonders of Social Media to reconnect me to my old stomping ground. |

- Who uses it, how often, and why?

- Can it be used for change or to change minds?

For example,"The Network in the Garden: Designing Social Media for Rural Life," by Eric Gilbert, Karrie Karahalios, and Christian Sandvig looked at rural vs. urban social media users. Turns out that rural users matched up with the researchers expectations on most counts: they had fewer "friends" (as in Internet contacts, not actual in-person friends), those "friends" were geographically closer to the users, more users were women, and more profiles were kept private.

Another example is in "Dynamic Debates: An Analysis of Group Polarization Over Time on Twitter," by Sarita Yardi and Danah Boyd (you'll see her name a lot in social media research - sometimes traditionally capitalized and others all lowercase). They studied whether Twitter users of a particular slant or viewpoint would engage mostly with users of similar views or if they sought out alternate viewpoints. Not surprising to me they found that the old saying holds true, "birds of a feather flock together."

As I sit here tonight thinking about social media and its users, I just have to look at my own profile pages to see the results of these studies. And I can't help but think these articles studied the wrong things. Social science research has been done for decades now, and we're fairly well researched in the human condition. Why is it so surprising that we'd "follow" or "friend" people who share similar interests and beliefs? Or that rural users would be more cautious or private?

I don't think we should study social media as this new and strange thing, putting its users under microscopes or back on psychiatrists' couches; technology is an extension of humanity - it's not going to change how we behave. Rather, I think it will capture our behavior like a snapshot and keep it for posterity. Those are the implications that should get some attention.

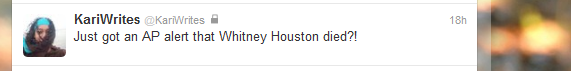

The readings for this week essentially summed up that people use social media for various reasons including narcissism and news dissemination. Who we "friend" and "follow" tell a lot about a person. Tonight, social media tells me that I didn't need to watch the Oscars (or the 500, if it weren't postponed), that's what I have friends and followers for. And they're telling me Christopher Plummer is having a good night: